Why Do We Need to Exercise?

Fitness

Hopefully it’s common knowledge by now that exercise is not only beneficial but essential for your health. There are many places you can learn about the benefits of this kind of exercise or that kind, but to my mind something that’s rarely well explained is why we actually need to exercise at all.

Adaptability

Specialism is great in an environment that requires the specialism, but terrible in all others. The most successful species in nature are those which can adapt to changing environmental demands. Because of this, life as it exists today is highly adaptable, within certain limits. The ability of biological systems to adapt to stimuli they receive - to become better at meeting the same challenge next time - is miraculous.

When you exercise, chemical reactions that take place during the activity trigger a cascade of other effects, leading - with nutrition and rest - to the tissues involved adapting to the stimulus. This adaptation is specific to the stimulus applied: if you exhausted yourself with a long cycle, your leg muscles' ability to resist fatigue will improve. If you lifted heavy weights, more contractile proteins will be laid down and the nervous system’s ability to use more of the muscle at one time will increase.

But nature is ruthless, and until recently, the availability of food could not be guaranteed (for some, it still can’t). Muscle tissue is expensive, even if you’re not using it. This logic applies to strengthening of the heart and bones as well, and is why we observe that humans respond to physical training, but will revert to their previous condition if training ceases.

If this balancing mechanism was not present, our evolutionary line would have failed: strenuous prehistoric lives would lead to more and more muscle that would be impossible to feed.

Interdependency

This is all well and good, but what’s not usually considered is that the metabolic processes that support this adaptability are deeply interwoven with the rest of our physiology. Biological systems are heavily interconnected, much more so than ones humans design.

One of the things humans have evolved to do well is output a lot of work over a long time, most likely for persistence hunting. These systems, such as the relationship between blood glucose and insulin, or the balance between bone formation and resorption, among many others, have evolved to require both sides in order to function. The way to stimulate both sides is - you guessed it - to exercise.

These systems make up the core part of our physiology - exchange of energy with the environment - so they can’t be neglected. With this and the “use it or lose it” nature of physical adaptation, the implication is clear: the price of being able to do something is that you must do it, and none of us can now opt out of this trade.

Balance

You can think of metabolism as having two sides - the Exercise side and the Feeding side. On the Exercise side, the body uses stored energy and incurs damage to its tissues. This is balanced by the Feeding side, where consumed food is used to replenish the stores and lay down new tissue. Both are obviously happening all the time, but the balance swings back and forth as you exercise, eat, sleep etc.

The point is that the chemistry of each side doesn’t work particularly well when the other doesn’t happen enough. They require each other: to oscillate between the two sides is better than to stay in the middle. If you burn 300 extra calories in a day and eat an additional 300, there will be no effect on your weight, but you will be healthier than if you did neither.

Type-2 diabetes happens when the body becomes insensitive to insulin, i.e. becomes unable to reduce its blood sugar level. This has a number of causes, but the most important one is persistently high blood sugar (over-Feeding). The most effective way to increase insulin sensitivity is regular strenuous exercise.

Atrophy

If you don’t use something, it will be salvaged, to conserve resources. For example, unused muscles will shrink (muscular atrophy), unloaded bones will weaken (osteoporosis), and an unused brain will become rigid and slow down (Alzheimer’s).

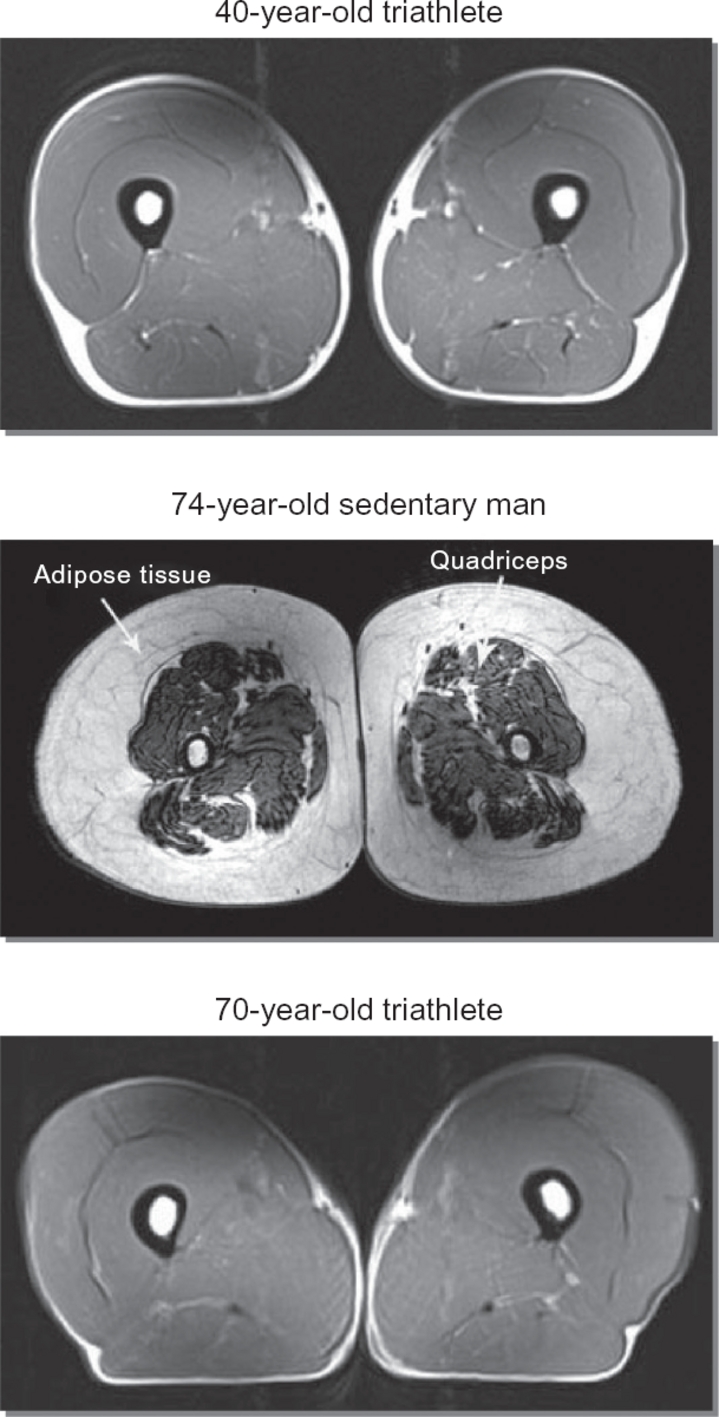

The cost of inactivity-related atrophy is therefore much greater than just looking less muscular. They say that you don’t stop moving when you get old; you get old when you stop moving. Here are some cross-section scans of the thighs of three different people:

In the middle image, the high quantity of fat, scraggly muscle and infiltration of fat into muscle are all signs of declining health. In fact, muscle strength and mass are good predictors of remaining healthy lifespan in the elderly.

Notes

This post was adapted from my answer to this StackExchange question, and as I said in my answer I’d strongly recommend reading Survival of the Fittest by Mike Stroud. I first read this in my final year of university (studing sport & exercise science) and found it helpful in unifying all the facts I’d been learning.